This psalm should remind us that deportations are one of the oldest and most effective methods that an imperial state might apply to establish control over a newly conquered territory and the population living within that territory. Three millennia ago, the Babylonians, but especially the Assyrians, builders of great empires centered in ancient Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq, benefited extensively from deportations from one point of their possessions to another: for example, 130 years before Nebuchadnezzar's deportation, Assyrian kings deported others Jewish people from Samaria, this time to northern Iraq, and brought other deportees on their places, especially from the other end of the empire, from the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian Plateau, which eventually resulted in significant ethnic and cultural changes within the region.

The benefits of deportations for imperial states are evident. Basically, they destroy possible resistance networks left after the conquest of the territory by eliminating the elites that could lead them, sowing terror among the conquered population left in the territory of their ancestors, opening the way to confrontation between its members interested in occupying seats, remained vacant after the deportation of elites. Conquerors can benefit from this kind of confrontation. Deportations are also an important source of free labor, and sometimes even contribute to the creation of large groups of loyalists among deportees.

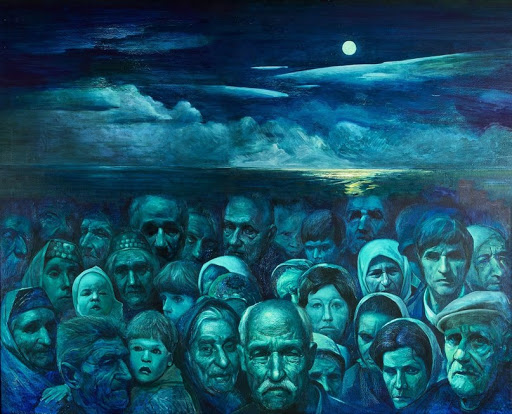

It is not surprising, therefore, that deportations have been adopted as a method of establishing domination over time by many other empires, including the Russian Empire, whether Tsarist or Bolshevik, which has improved this method, from a historical point of view, to unprecedented efficiency, but from a moral point of view, to a truly diabolical form. The Russian Empire's approach to this method is not accidental, given the vast Siberian territories that it had to control and exploit, and the deficiency of natural barriers in its European territories, which forced Russian leaders, including for strategic reasons, to implement extreme methods of rapid and complete conquest of conquered groups. As a result, the Circassians, Tatars, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Poles, Lithuanians, Romanians, Germans, Georgians, Armenians, Azerbaijanis and many others became victims of Russian deportation.

Similar to any sword, deportations also have two edges. When the social structures of the conquered population are too extensive and entrenched to deport elites to disorganize them, deportations not only do not eliminate resistance, but they can reinforce it through insults created by those who have been disconnected from parents, siblings, friends, forced to other lands. The mental resistance of deportees might also be strengthened, even in harsh conditions of forced exile. “May my tongue stick to the roof of my mouth if I fail to remember you, if I do not make Jerusalem my greatest joy!” - the deported Jews swear by faith in their own homeland, and then conclude Psalm 136 with vengeance and fury: “O daughter of Babylon! Happy shall he be, that rewardeth thee as thou hast served us. Happy shall he be, that taketh and dasheth thy little ones against the stones”. In particular, the return of deportees to favorable historical conditions may lead to an alliance in the form of higher resistance of an individual one among deportees and those among whom they were deported. Should we not forget that the ancient masters of deportations, the Assyrians, were practically vanished from history until the almost complete disappearance of two groups, among whom they deported many people to all parts of the empire: the Babylonians and the Medes, the Iranian nationality.

In addition to the vengeful spirit they have created toward the conqueror, deportations, which fail to overcome the resistance of the conquered population, have another important effect: strengthening the internal cohesion of nations, which manage to overcome this traumatic historical experience, summarizing and providing them with a higher valence on the basis of their collective memory and national identity. The deportation of the Jews to Babylon, remembered in many other songs and works outside of Psalm 136, was crucial to the ancient Jewish identity, contributing to the effectiveness of later resistance to the Seleucids and Romans and the ability to endure a second great exile, lasting for nearly 2,000 years. This was also due to favorable historical circumstances, but especially to the Jewish intellectual elite, which, unlike other elites of the ancient East, managed to cultivate the traumatic experience of exile and transform it into what the French historian Pierre Nora defined as lieu de mémoire, “the place of remembrance”, with the meaning of “significant entity, tangible or intangible, which due to human will, or as a result of time has become a symbolic element of community memory”. Consequently, memory might be considered as a constant theme of Psalm 136: “We sat down and wept, as Zion remembered”; “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget its skill”; “Remember, O Lord, the children of Edom in the day Jerusalem’s fall!”

To what extent do these observations about the double-edged sword of deportation affect the region between the three seas today, and especially the relationship between the Baltic and Black Seas? Of course, to a large extent, if we consider at least the courageous resistance of the Crimean Tatars, victims of some of Stalin's most terrible deportations, who are now forced to live in Russia's annexation of Crimea in 2014, it is the clearest illustration of revived Russian imperialism. The three great waves of deportation from the Moldavian SSR (June 12-13, 1941, July 5-6, 1949, and March 31-April 1, 1951) remain in the Republic of Moldova as one of the most frequently used historical landmarks in oppositional discourse to foreign policy to Russian external policy, surpassed only by the memory of the separatist war of 1992 in Transnistria.

It is most probable that there will be no deportation trial in Nuremberg concerning the Russian Empire, whether Tsarist or Bolshevik. It will not be necessary for history to do justice, provided that two conditions are satisfied. The first is that the intellectual elite of every population traumatized by Tsarist or Bolshevik deportation must continue to cultivate their memory (for other similar crimes in particular) and change them to a “place of memory”, an inviolable milestone in collective memory about the national capacity for solidarity, revival and overcoming the difficulties of history. Second, the “places of remembrance” of each aggressor between the Baltic and Black Seas were recognized and respected by other groups affected by such actions. Without mutual recognition and sincere sympathy for such massacres as Katyn against Poles, Vinnytsia against the Ukrainians, Bila Krynytsia against the Romanians and the deportations that accompanied or followed them, “places of memory” created by each nation separately will never be united to the Eastern European “place of memory”, which will always compel us to realize that our destinies are chained to good and bad events, as they have been considered since the Great Mongol Invasion. Consequently, I would like to conclude with a suggestion: when the general Eastern European virtual museum dedicated to the deportations (and other crimes) of the Bolshevik regime?

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the editorial staff.